Scientists trigger 'grenades' in the body to kill cancer cells

Scientists from the United States have developed microscopic grenades that will explode directly in tumours and release cancer-killing payloads to kill harmful cells. The grenade explodes through heat-sensitive triggers and delivers drugs directly to the tumour without harming healthy tissue. The technology could lead to new kinds of treatment, scientists say.

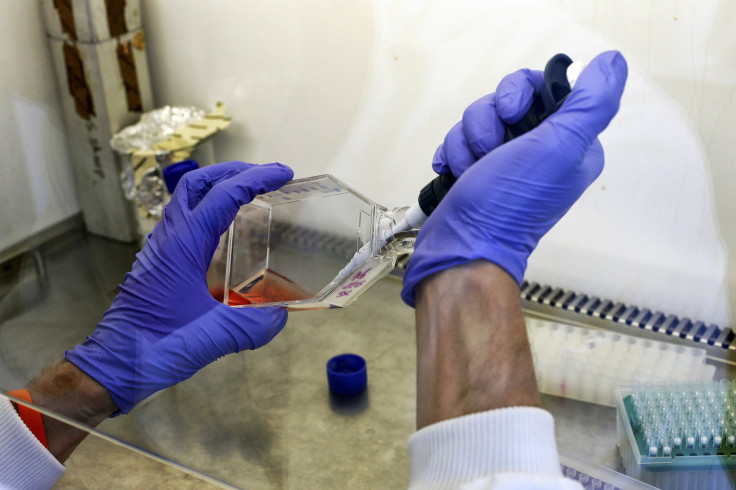

The grenades, called liposomes, are tiny bubbles of fat that carry drugs to cancer cells. The bubbles were designed to avoid delivering side effects to patients by ensuring the drugs hit only the tumour, according to the designers from the University of Manchester.

The technology was described as the "holy grail of nanomedicine." In two new studies, scientists found that by increasing the temperature of the tumours in animal models, they can control the pin to trigger the cancer-killing grenades when approaching the target and releasing the drug, BBC reports.

"These studies demonstrate for the first time how they can be built to include a temperature control, which could open up a range of new treatment avenues,” Professor Charles Swanton, the chairman of the conference, said in a statement.

Initial tests were conducted on mice with melanoma where the grenades caused tumours to accept the drugs better than any treatment. The "greater uptake" of drugs caused moderate improvement in survival rates of the patients, the researchers said.

The liposomes were designed as water-tight at normal body temperature and become leaky when the temperature increases to 42°C. The researchers believe that the temperature-sensitive liposomes could potentially travel safely around the body due to its bubble-like structure while carrying the designated cancer drug.

“Once they reach a 'hotspot' of warmed-up cancer cells, the pin is effectively pulled and the drugs are released,” said Kostas Kostarelos, the study author and Professor of Nanomedicine at the University of Manchester. The findings will be presented at the National Cancer Research Institute conference in early November.

However, the researchers said that further studies are needed to understand how the grenades will effectively work on different types of tumour and explode directly to its target to kill cancer cells. Kostarelos said that there are ways to potentially heat cancer cells in patients that are already in clinical use, but he did not mention any potential procedure.

Contact the writer at feedback@ibtimes.com.au or tell us what you think below.