Scientists move forecast of 2 black hole collisions ahead to 100,000 years

Astronomers at Columbia University moved earlier its forecast of the collision of two black holes to 100,000 years from a previous prediction that the galactic event would happen 20 light years away. Scientists have been observing these two galaxies and their black holes that are moving around each other at a distance of one light-week.

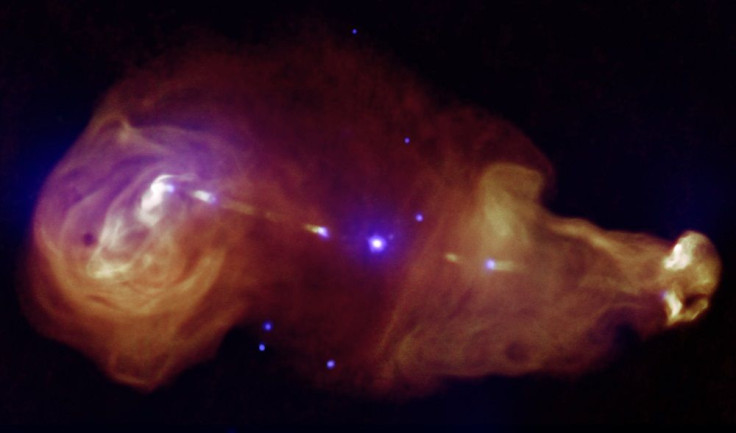

The evidence is PG 1302-102, a quasar, observed to have a rhythmic flickering from its galaxy’s nucleus. Most of the light from the quasar comes from a big disc of gas surrounding the smaller of the two black holes, reports The New York Times.

The change is the forecast of a mashup date happened after the astronomers made some calculations on the two galaxies in the Virgo constellation. Zoltan Haiman, senior author of the study, said this is the closest that scientists have to observing two black holes likely to result in a massive collision, reports CNET.

“Watching this process reach its culmination can tell us whether black holes and galaxies grow at the same rate, and ultimately test a fundamental property of space-time: its ability to carry vibrations called gravitational waves, produced in the last, most violent, stage of the merger,” Haiman explains in the study published in Nature journal.

If the collision takes place, it would release energy equal to 100 million supernova explosions. To further illustrate the massiveness of that event, Haiman says it’s similar to lighting a pile of TNT with a mass of 100 quintillion planet Earths which would release the same amount of energy.

The gravitational waves, which could be traced to the Big Bang, the original cosmic explosion, allows scientists to study the secret of gravity and test Einstein’s theory on black holes, according to Daniel D’Orazio, lead author of the study. He acknowledges that the present crop of scientists would not be around to observe the massive collision take place, but their study would improve the means of finding other black hole pairs.

In Einstein’s general theory of relativity, he says objects so dense do not allow light to escape. Every galaxy apparently has a supermassive black hole that weighs millions or billions of times as the sun which burps sparks of half-eaten stars and gas.

Contact the writer at feedback@ibtimes.com.au or tell us what you think below