Eye Stem Cell Therapy: First Clinical Trial Successful In Asia

In a recent development, a team of scientists in Korea has successfully injected human embryonic stem cell (hESC)-derived retinal support cells into the eyes of four men suffering from macular degeneration.

Macular degeneration is an age-related medical condition that usually affects older people ( over 50 years), resulting in loss of vision caused due to the damage to the visual field or the macula .It is one of the leading cause of blindness and visual impairment with about 30-50 million people suffering from it globally. The diseased are unable to read or recognise faces, however, they can carry on with their other activities of daily life since their peripheral vision remains intact.

The researchers for their study treated two men, aged 65 and 79, with dry age-related macular degeneration, while a 40-year-old man and a 45-year-old man were both treated for Stargardt macular dystrophy, an earlier-onset inherited disease. The results of the study, published in the journal Stem Cell Reports, showed that among the four, the three men experienced vision improvements in their treated eyes after a year of following the procedure, while the fourth man’s vision did not show much improvement.

The clinical trial was initiated by a Korean company CHA Biotech, whereas Ocata provided the hESCs and some methodological instruction. Robert Lanza, the study co-author and chief scientific officer at Ocata, says, “Together with the results here in the US, I think this bodes well for the future of stem cell therapies.”

The success of the clinical trial has raised hopes for the scientist working in the field of regenerative medicine by providing a strong evidence that injecting hESC-derived cells is feasible and might be of therapeutic use in the future.

Earlier in 2012 and 2014, there were similar studies published in The Lancet which demonstrated that hESC-derived cells could be injected into the space behind the retina safely in patients suffering with macular degeneration.

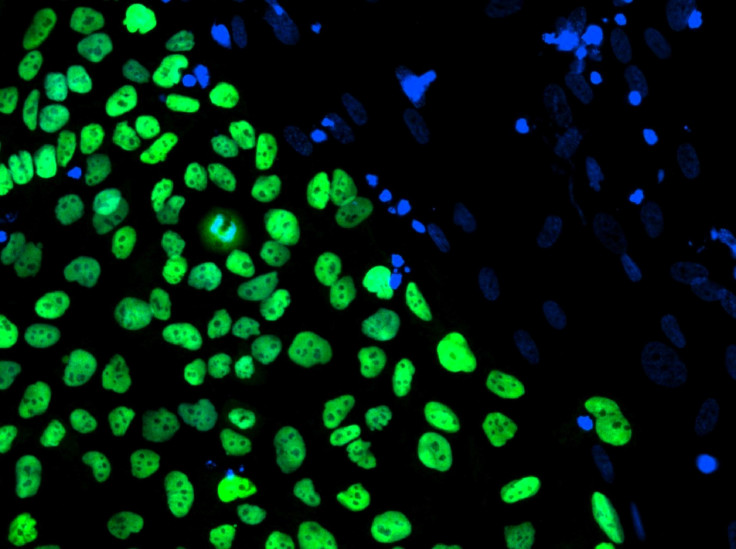

Since the size of the trial carried out was small, Lanza feels that it is too early to conclude whether the treatment systematically improves vision in patients. However, he went on the record and said that the patients did experience vision improvements because of the infusion of new retinal pigment epithelium, or RPE, cells which otherwise are destroyed by macular degeneration.

Another significant discovery made by the team was that the transplanted RPE cells did not form tumours or differentiate into other type of cells. To this, Lanza adds, “Regulators don’t really want to see a tooth in the eye or they don’t want to see beating heart cells in the wrong place.”

On careful screening, the researchers were successful in avoiding the transplant of the cells that were not fully differentiated and hence did not form any unwanted tissues. Also, the patients’ immune systems did not reject the transplanted cells.

To contact the writer, email:ruchira.dhoke@gmail.com