Virus, What Virus? India Gets Back To Work

India is on course to top the world in coronavirus cases, but from Maharashtra's whirring factories to Kolkata's thronging markets, people are back at work -- and eager to forget the pandemic for festival season.

After a strict lockdown in March that left millions on the brink of starvation, the government and people of the world's second-most populous country decided life must go on.

Sonali Dange, for instance, has two young daughters and an elderly mother-in-law to look after. She was hospitalised this year in excruciating pain after catching the coronavirus.

But after the lockdown exhausted the family's savings, the 29-year-old had to return to work at a factory where she earns 25,000 rupees ($340) a month.

"Now that I have recovered, I am no longer so scared of the disease," she told AFP amid the din of machinery at the Nobel Hygiene plant east of Mumbai.

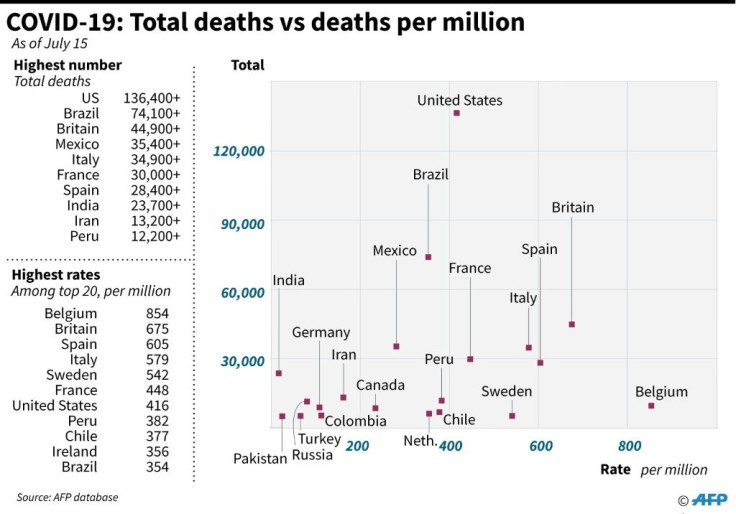

The pandemic's confirmed fatality rate has been heaviest in richer nations with older populations -- the US death toll is double that of India despite having only a quarter of the population.

Poor countries have suffered far worse economic pain, with the World Bank predicting 150 million people could fall into extreme poverty worldwide.

Many children in the developing world are now working to help their parents make ends meet, activists say, while thousands of young girls have been forced into marriage.

In Varanasi in northern India, 12-year-old Sanchit no longer attends school and instead collects cloth discarded from bodies before cremation on the city's ghats.

"On a good day, I earn around 50 rupees (70 US cents)," the boy told AFP.

The IMF projects India's GDP will contract by 10.3 percent this year, the biggest slump of any major emerging nation and its worst since independence in 1947.

When India went into lockdown, it was a human catastrophe, leaving millions in the informal economy jobless, penniless and destitute almost overnight.

No one wants to go back to that, said Gargi Mukherjee, 42, as she shopped in the New Market area of Kolkata, thronging with festival-season customers, many without face masks.

"For survival, people have to come out and do their jobs. If you don't earn, you cannot feed your family," she told AFP.

Experts caution that the October-November season -- when Hindus celebrate major festivals such as Durga Puja, Dussehra and Diwali -- may trigger a sharp increase in infections, as consumers crowd markets to snap up big-ticket items on discount.

"Of course corona is to be feared. But what can I do? I can't miss the moments of Durga Puja," said housewife Tiyas Bhattacharya Das, 25.

"Durga Puja comes once in the year, so I cannot miss the enjoyment of the shopping."

Sunil Kumar Sinha, principal economist at the Mumbai-based India Ratings and Research agency, said Indians faced a stark choice.

"People have to choose whether to die of hunger or risk getting a virus that may or may not kill you," he told AFP.

Indeed India's relatively low mortality rate -- about 1.5 percent of its more than seven million cases -- has surprised many who warned coronavirus would lay waste to its crowded cities, beset by poor sanitation and crumbling public hospitals.

Even accounting for some likely undercounting, it is evident that the nightmare scenario of dead bodies piled in the streets as seen during the 1918 flu pandemic has mercifully not materialised.

The unexpected reprieve has given Prime Minister Narendra Modi leeway to resist a fresh lockdown, with the human toll -- and political cost -- of another shutdown higher than seeing case numbers soar.

But Bhramar Mukherjee, an epidemiologist at the University of Michigan, warned the government should not simply let the virus run its course.

"In order to open up, you need to intensify public health measures... If you completely take your foot off the brakes, the virus will take off too," Mukherjee told AFP.

Last month, the Indian Medical Association slammed the Modi government for its "indifference" to the sacrifices of front-line staff in one of the world's worst-funded health care systems.

"It appears that they are dispensable," it said.

Back in Kolkata, bookseller Prem Prakash, 67, was philosophical.

"You have to leave some things to fate," he told AFP.

"Fearing death too much is not a solution. When that comes, you should accept it gracefully."