How A Dictatorship-era Constitution Endured In Chile

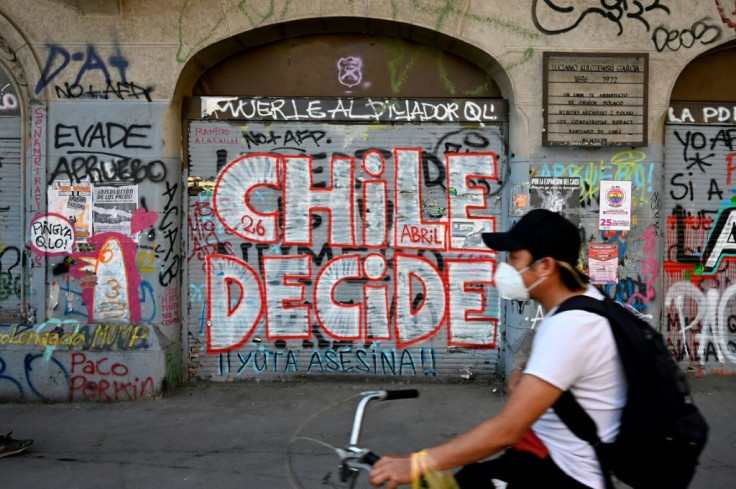

Replacing Chile's dictatorship-era constitution was a pressing demand from the streets during months of social protests in Chile in 2019.

On Sunday, Chileans will vote in a referendum to approve or reject changing the constitution; and if they approve, what kind of body should draft it -- a mixed assembly composed equally of lawmakers and citizens, or a Constituent Convention made up of elected non-political citizens.

But how is a constitution drawn up under a dictatorship still in force in modern-day Chile?

Dating from a September 1980 referendum under military ruler Augusto Pinochet, the text was drafted by law professor and far-right senator Jaime Guzman.

Tailor-made to bolster conservative sectors of society even after the end of the dictatorship, "it was designed to have a moderate democracy... where a conservative minority group can always exercise a veto," says Chilean historian Cristina Moyano.

Meaningful change was difficult under Chile's binomial electoral system, which allowed conservative parties to be over-represented in Congress, ensuring the necessary two-third or three-fifths majorities required for change were never reached.

While the system promoted political stability during the transition by favoring the two major opposing coalition blocs, minorities had few possibilities to win representation in Congress.

In such a political climate, Pinochet retained significant political weight in the transition to democracy, remaining commander-in-chief of the armed forces until 1998 and a senator until 2001.

During the transition, democratic parties had to accept the 1980 constitution, according to Domingo Lovera, professor of constitutional law at Santiago's Diego Portales University.

"There had to have been political prudence in order for the transition to take place," he said.

The binomial electoral system was finally reformed under the left-wing presidency of Michelle Bachelet in 2015 in favor of a proportional representation system.

Chileans have amended their constitution many times since 1990, though never in depth.

The charter's most anti-democratic principles were eliminated in a 2005 revision under center-left president Ricardo Lagos, who had managed to forge a broad political agreement.

The changes meant senators in Congress had to be elected, and not merely appointed, and military chiefs could for the first time be dismissed without the prior agreement of the National Security Council, which now has only an advisory role.

Leftist and centrist political parties, as well as various social movements, say the current constitution is an obstacle to the deep social reforms needed in Chile.

"It sets up a series of obstacles so that popular will cannot become a reality," summed up Socialist Party president Alvaro Elizalde.

"The constitution has established principles that limit state action," and instead promotes private health care, education and the pensions system, says Sebastian Zarate, professor of constitutional law at the University of the Andes.

During the long months of social protest, demonstrators demanded the state be made to take more responsibility for the middle class and poor struggling with low incomes, and that the universal right to health care and education be enshrined in the constitution.

Should Chile vote for change on Sunday, and choose the option of a Constituent Convention, composed solely of people outside professional politics -- its composition will be split between men and women, a world first.

Congress approved an unprecedented law in March that guarantees parity of candidates for an eventual Constituent Convention.

bur-lab-jb/db/mdl