UK astrophysicists unravel merging black holes

The mystery on what really happens when black holes collide and create space-time ripples has started to unravel. Scientists recently observed gravitational waves arising from the collision of two black holes around 1.3 billion light years away from Mother Earth.

An upgraded Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (Advanced LIGO) detected gravitational waves from two binary black hole mergers. University of Birmingham, UK astrophysicists also developed a toolkit/platform named COMPAS for the statistical analysis of observations of the massive binary evolution.

The use of the Compact Object Mergers: Population Astrophysics and Statistics (COMPAS) was recently featured in Nature Communications. Senior author of the paper Ilya Mandel stated that just as a palaeontologist who has never seen a live dinosaur can determine how the prehistoric animal appeared and lived based on its fossil, the astrophysicists can analyse the phenomenon of merging black holes. First author Simon Stevenson, a PhD student at the University of Birmingham, noted the value of COMPAS in allowing them to meld all their observations and unravel the puzzle of merging black holes that thereafter send space-time ripples seen by LIGO.

Massive stars, which are the precursors of the black holes that LIGO has observed, expand to a large extent in the course of their evolution. The key challenge, then, is how to fit such colossal stars within a very small orbit.

The University of Birmingham website that featured the astrophysicist’s statement shed greater light on how stars interact during their fleeting but intense lives. It turns out two massive stars start out at a wide distance from each other. As they expand, they interact and engage in numerous episodes of mass transfer.

The stellar cores are enveloped in a dense cloud of hydrogen gas by a very swift, unstable mass transfer. The stars then get close together for gravitational-wave emission to be efficient.

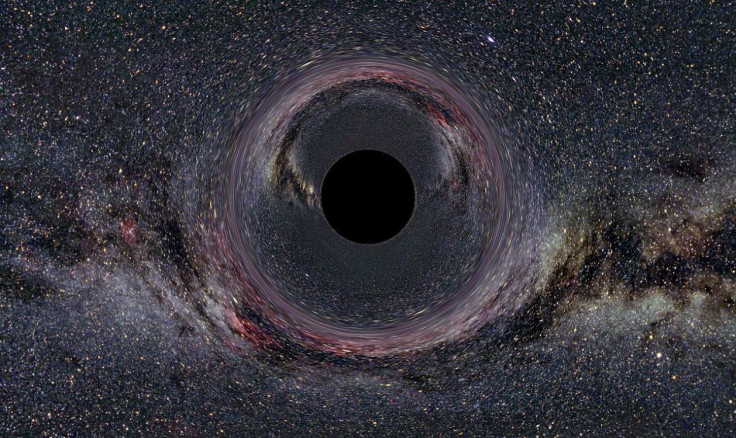

In related news, an international team of astronomers have set out to connect a number of telescopes on Earth with the end in view of making the first ever image of a black hole. The astronomers may possibly see the shadow of the black hole's event horizon set against the awesome backdrop of brightly shining swirling material.

UK-led European astronomers utilised the MUSE and X-shooter instruments on the Very Large Telescope that made the recent observations possible. The telescope facility is operated by the European Southern Observatory on Cerro Paranal in Chile.

The group observed the colossal winds of material emanating near the supermassive black hole at the heart of the southern galaxy, uncovering the first clear evidence that stars are being born within them. This was shared by the European Southern Observatory in a statement.

From @physorg_com: Scientists make progress on unravelling the puzzle of merging #BlackHoles https://t.co/p9itfpBMX8 #spacenews #space pic.twitter.com/PPa0Dd7YKC

— Perth Observatory (@perthobs) April 9, 2017