New sponge-like implant sucks, curbs spreading cancer cells in the body

A new small, sponge-like implant has been invented in the US as device to detect and trap cancer cells, to prevent it from spreading to other areas in the body. The device has unexpectedly reduced the numbers of circulating tumour cells, or CTCs, present at other sites of the body.

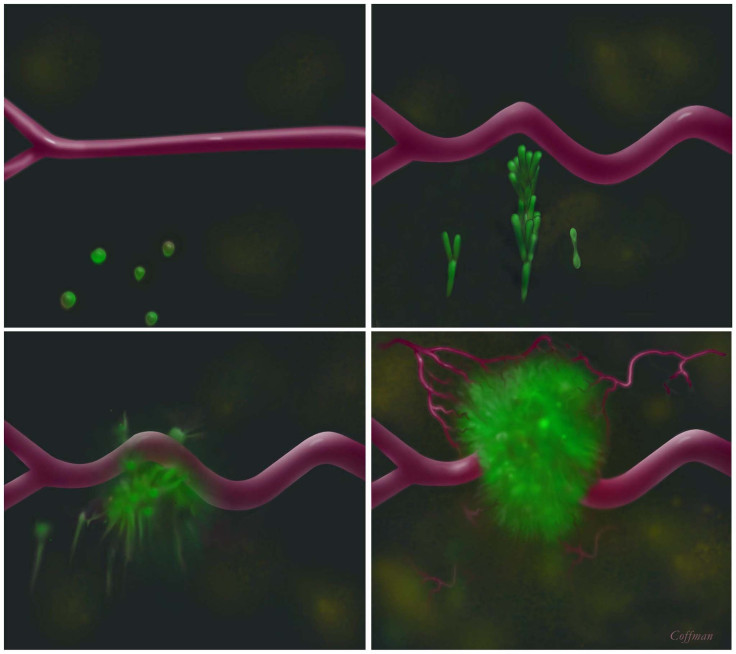

The implant, so far tested in mice with breast cancer, would serve as an early warning system in patients, giving a warning to doctors before cancer spreads and new tumours could grow in the body. The study, published in the Nature Communications, shows the implant were used in a process where immune cells attract loose cells spread to other areas in the body from an initial tumour.

The researchers said that the immune cells used to set up camp on the implant, pulling the cancer cells. They also found an unexpected result after measuring cancer cells that had spread in mice with and without the implant, which the sponge-like device did not only attracted and captured the CTCs but also reduced its numbers that migrated to secondary sites from the initial tumour.

"Animals receiving an implant had a significantly reduced burden of disease in their lungs relative to animals that did not have an implant," lead researcher Lonnie Shea, a professor at the University of Michigan, told AFP.

According to the Cancer Research UK, the cancer cells breaking off from a tumour to grow in other areas of the body cause nine in 10 cancer deaths in the population. The CTCs spread in sites such as in the bones, liver or lungs that commonly appear to be difficult to detect until a new tumour has formed, with some patients showing no cancer symptoms before it's too late.

The implant is about five millimetres in diameter, made from a "biomaterial" already being used in other medical devices. In the experiments, the researchers implanted the device in the abdominal fat or under the skin of the mice.

The team used a special imaging technique effective to detect cancer cells that had been caught in the implant, and to distinguish the circulating cancerous and normal cells. The researchers are also planning to conduct the first clinical trials to humans in the near future, according to Shea.

Shea and his team aim to analyse if the spreading cells will have the same reaction in the implant in humans like in the mice. He added that the team wants to determine if the same imaging technique would be safe for humans to detect cancer cells.

"We urgently need new ways to stop cancer in its tracks,” said Lucy Holmes, Cancer Research UK's science information manager. "So far this implant approach has only been tested in mice, but it's encouraging to see these results, which could one day play a role in stopping cancer spread in patients."

The work in animals was being continued by the researchers to see the overall outcome if spreading cancer cells were detected at a very early stage. But the process of spreading cancer cells was not yet fully understood.

To date, metastasis, or the process of spreading cancer cells, is a huge problem for people suffering from cancer. The process causes about 90 percent of human cancer deaths around the world, and even if the implant works in humans, it could only alert doctors about the presence of cancer cells but not to eradicate all the CTCs from the body.

Contact the writer at feedback@ibtimes.com.au or tell us what you think below