Music could potentially help epileptics prevent seizures: Study

Seizures could be prevented with music as new potential therapies for people with epilepsy, a study suggests. The finding shows the brains of people with epilepsy appear to react to music differently from brains of those who do not have the disorder.

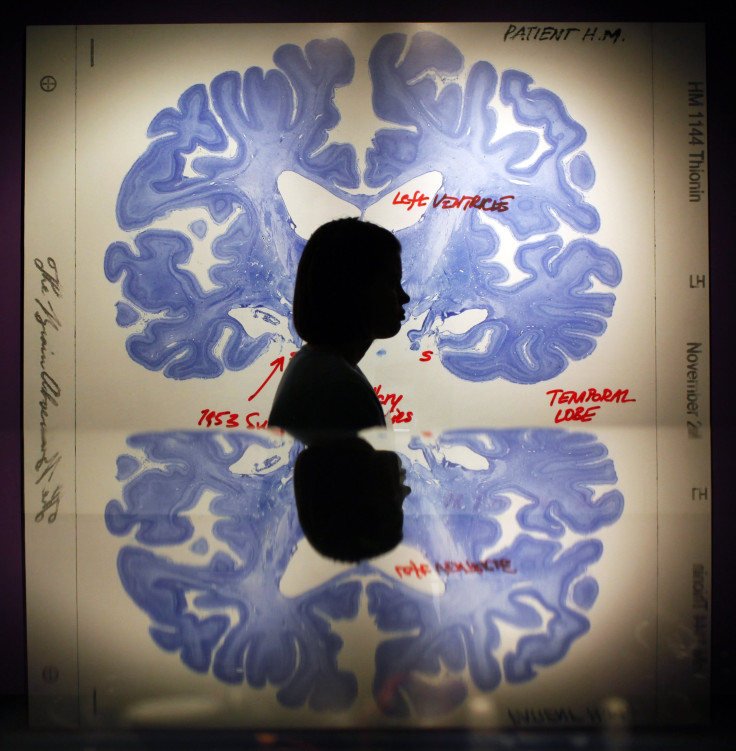

According to a research paper presented at the American Psychological Association’s 123rd Annual Convention, approximately 80 percent of recorded epilepsy cases are temporal lobe epilepsy, in which the seizures appear to originate in the temporal lobe of the brain. The auditory cortex in the temporal lobe is also the area of the brain where music is processed.

Researchers compared the musical processing abilities of the brains of people with and without epilepsy using an electroencephalogram to study the effect of music on the brains of people with epilepsy. They have attached electrodes to the scalp of the participants to detect and record brainwave patterns.

The patients’ brainwave patterns were recorded while listening to a 10-minute silence, followed by either Mozart’s “Sonata for Two Pianos in D major,” andante movement, or John Coltrane’s rendition of “My Favourite Things.” After that, researchers repeated two more 10-minute silence, but each followed by randomised musical pieces.

The result shows significantly higher levels of brainwave activity in epileptic participants while listening to music. Their brainwave activity tended to synchronise more with the music, especially in the temporal lobe than in people without epilepsy, said Christine Charyton, adjunct assistant professor and visiting assistant professor of neurology at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Centre, who presented the research.

“We were surprised by the findings… we hypothesised that music would be processed in the brain differently than silence,” Charyton stated.

In the study, 21 of the participants were patients in the epilepsy monitoring unit at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Centre between September 2012 and May 2014. With the proven conditions of the patients in the study, researchers believe the finding could prompt the development of new therapies to prevent seizures.

Contact the writer at feedback@ibtimes.com.au or tell us what you think below