Ebola returns to Congo for the 10th time: here's what we know

Barely a week after declaring the end of the ninth Ebola virus outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), officials announced another in the North Kivu and Ituri Provinces, in the eastern part of the country. The Conversation Africa’s Ozayr Patel spoke to Jacqueline Weyer to found out more about the 10th Ebola outbreak in the country.

Where has the outbreak happened and what are the challenges in making sure it’s contained?

The current outbreak is reported from the eastern provinces of North Kivu and Ituri. These are remote locations with a distance of more than 3000 kilometres separating them from the capital of Kinshasa. The provinces border Uganda and Rwanda and measures are being put in place to prevent the disease spreading across the border.

There are quite a few challenges to managing the outbreak. One of them is that this part of the DRC has been politically unstable for 20 years. This will, however, not be the first outbreak happening and being contained in conflicted territories.

Can the country employ the same tactics it’s used before to battle this outbreak?

Historically, containment efforts during these outbreaks have included tracing and monitoring anyone who has had contact with someone who is known to have contracted the Ebola virus. In addition, known cases of the Ebola virus disease are isolated to curb the spread of the disease.

The premise of these efforts is to essentially get ahead of the virus’s chain of transmission, and to break it. These methods are still effective and continue to be the mainstay of containment efforts.

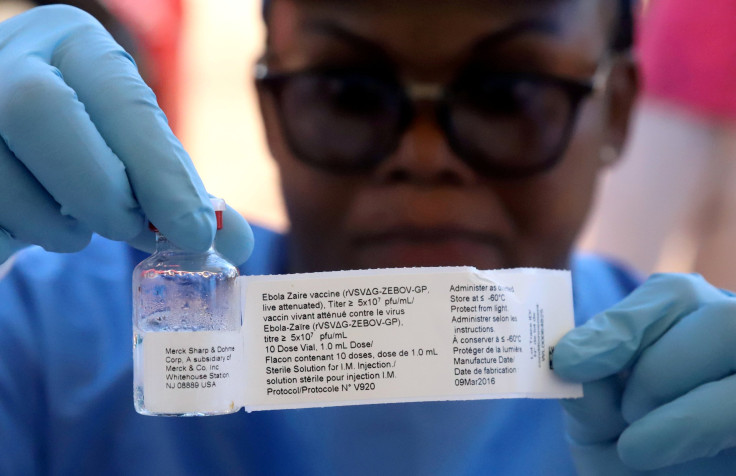

In addition to this classic approach health officials now have a vaccination to support outbreak management.

Several candidate vaccines have been developed for the Ebola virus. They remain at different stages of clinical trails. One of these vaccines, used during the West Africa outbreak, was also employed during the previous Ebola outbreak in the DRC, with more than 3000 doses administered.

The vaccine is based on a benign virus that doesn’t cause illness in humans but provokes an immune response in the body without causing the disease - we call this type of vaccine a recombinant vaccine. The antibodies produced in response to this vaccination may then protect the recipient when an exposure happens.

Why has the DRC experienced so many outbreaks of Ebola?

Ebola is what’s known as a zoonotic disease – it can be transmitted from animals to humans. Although the natural ecology of the Ebola virus remains to be fully understood, scientists believe that the virus is naturally found in certain species of forest-dwelling bats. The virus can then be transmitted from the infected bats to other forest-dwelling animals, or to humans. Several outbreaks have been traced back to people who were very likely to have had contact with bush meat. Contact with raw blood and tissues of an infected animal is of particular concern.

Once the virus enters the human population it spreads through direct contact with the infected bodily fluids and blood of an an affected person. So, it is typically close contacts such as family and friends caring for the sick, who are at most risk. Burial rituals are also linked with the perpetuation of outbreaks as mourners have direct contact with the deceased. Health care workers are also at high risk of infection.

The ten outbreaks recorded from the DRC between 1976 and 2018 have not been reported from the same exact locations. This implies that the virus is widely spread in its natural reservoir throughout the DRC, which is heavily forested. But it also indicates that the spread to humans is seemingly a rare event.

Jacqueline Weyer, Senior Medical Scientist, National Institute for Communicable Diseases

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.