Commercially available training devices may impair cognitive ability

A latest study proved signs of impaired memory in people to whom low-intensity electrical stimulation is applied to the frontal lobe of the brain using a free, commercially available device. The recent research findings have discarded the previous thought that such devices actually stimulated the functioning of the brain when electrical impulses are applied using electrodes.

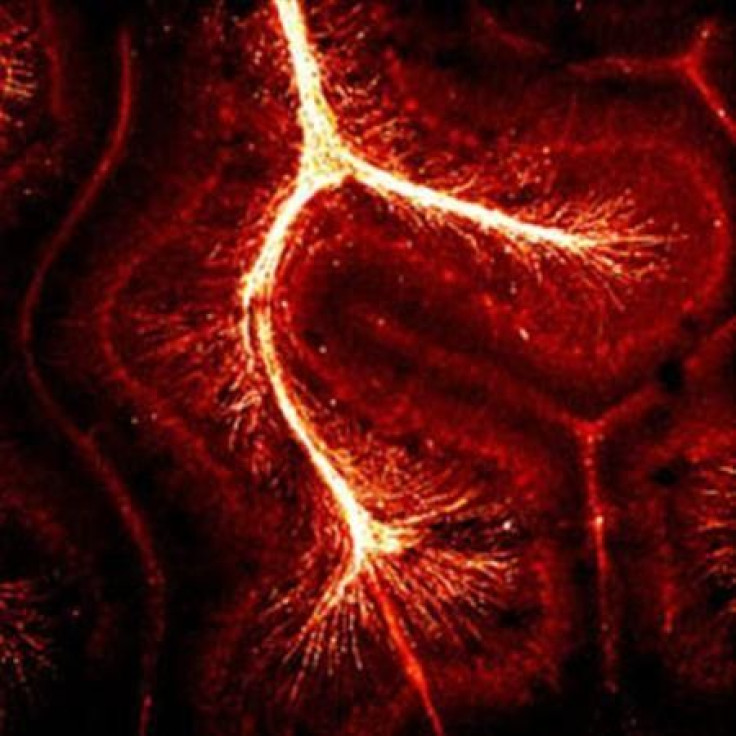

The researchers conducted their study using technology called transcranial direct current stimulation, or tDCS. The advanced technique is widely advertised by the media and even praised by the John Hopkins Medical School in the US.

During the study, a team led by psychologists Lorenza Colzato and Laura Steenbergen, studied the impact of tDCS, a non-invasive brain stimulation device , on the cognitive performance of 24 healthy participants. To one group of participants, the team administered low-intensity current to the frontal lobe, using a pair of electrodes. The other group of people received a fake stimulation on the frontal lobe.

The brain stimulation, as advertised, was expected to activate the neurons in the targeted region, promoting a greater cognitive ability. After applying the current, the researchers asked the participants to perform a working memory task in which they had to update the information they remembered, reports The News Medical.

The researchers found that the stimulation impaired the memory-related performance in the participants who actually received a low-intensity current. On the other hand, the control group showed the same memory performance as before.

"Even if preliminary, these results show the fundamental critical and active role of the scientific community in evaluating the sometimes far-reaching, sweeping claims from the brain training industry with regard to the impact of their products on cognitive performance," said Colzato in a statement.

Earlier in 2015, Jared Horvath of the University of Melbourne, Australia conducted a study to examine the effect of tDCS on working memory. Horvath was unable to conclude anything significant since the study results were too diverse to be interpreted.

Contact the writer at feedback@ibtimes.com.au, or let us know what you think below.