Cancer, Diabetes Detection Can Be Made Possible Through Home-Test Kits With Help From GM Bacteria

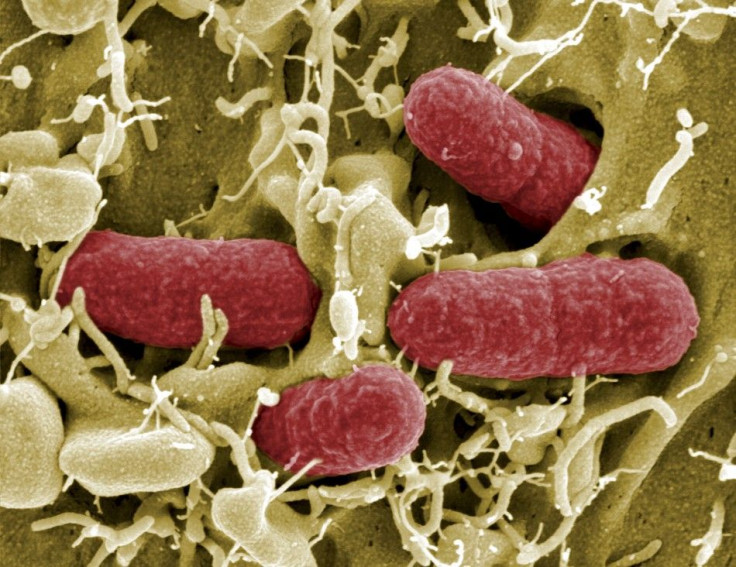

Bacteria may be notoriously known to cause diseases, but a new study shows that they can help detect serious illnesses such as diabetes and cancer. In two separate studies, scientists reprogrammed bacteria to be able to detect liver cancer and diabetes in mice and humans, respectively.

The experiment for the liver cancer detection was conducted by researchers from UC San Diego and MIT, while the diabetes detection was done by Stanford University and University of Montpellier in France. For both studies, researchers used a harmless strain of E. coli known as the Nissle 1917, which can be found in yogurt preparations.

In the first study, researchers improve E. coli’s ability to pass the digestive walls and gain access to the liver of the mice populated with cancer cells. The researchers found that the bacteria did not crowd around all tumours in the body, but only aimed at liver tumours, Science Daily reports.

The research paved way to a diagnostic technique specifically intended for liver tumours. Researchers also noted that no harmful side effects came to the mice when given with genetically-modified bacteria. According to Sangeeta Bhatia, study author and professor at MIT, this diagnostic technique can be used in patients who had their colon tumour removed because recurrence in the liver is most likely.

Meanwhile, the second study used the same signal-emitting E. coli bacteria to detect glycosuria, or presence of sugar in human urine, which signals uncontrolled diabetes, LA Times reports. The E. coli was able to change the urine colour to in nearly 89% of glycosuria cases.

Furthermore, the study found that the bacteria rarely gave false positive results. According to researchers, the bacteria’s ability to detect glycosuria without creating so much false positives made the technique almost as reliable as a basic urine dipstick.

“They are both nice advances for the field,” said Jim Collins, a synthetic biologist at MIT, in a report from Science News. However, Collins cautioned it would still take several years before both techniques will be accepted into clinical practise.

To report problems or leave feedback on this article, email: wendylemeric@gmail.com.